Hey V&V fam ✌️

I’ve been away for awhile, but excited to land back in your inbox with a new essay. Welcome to the 400+ subscribers reading this week. If you’ve found your way here but haven’t subscribed yet, join in👇

For a while now, I’ve wanted to write an essay about the state of user experience design — and the value of that design — from a non-technical perspective. A piece about UX that’s not necessarily written for designers or product people as a primary audience.

If we zoom out from viewing UX as a specialization or technical discipline, we can get a fresh perspective on both the realized and unrealized potential of great UX as a giant lever for value-creation.

Here’s the challenge: zoom out too far and UX becomes everything and anything. Once you start talking at the “experience” level, untethered from product or design jobs to be done, you find yourself talking about phenomenology, philosophy, the meaning of being in and moving through the world. Heady. Suspend the gravity of commercial objectives and constraints, and UX thinking might float you beyond any frame of practicality.

I do like to flirt with all things theoretical and philosophical — the vague — but there’s gotta be vivid takeaways to go all-in on an essay. I aimed to find a balance in this piece, exploring the following ideas:

I. Contemporary UX design is a symptom of the millennial tech upbringing

II. We’re awakening to less obvious, more abstract opportunities to reduce friction

III. Design is marketing, marketing is design [upcoming, to be published later]

I. Contemporary UX design is a symptom of the millennial tech upbringing

Typically, I don’t attribute much meaning to the differences we perceive between generational cohorts. Sweeping statements about generational differences tend to be hollow. As I’ve noted in several pieces this year, we’re seeing a lot of evidence that demographics are, increasingly, a weak or lagging indicator of the actual stratification within an audience (especially as it relates to media habits).

Here’s the part where I contradict myself.

I’m an “elder millennial.” I believe my peers and I belong to a very specific generational pocket; our tech upbringing and the relationship we’ve subsequently developed with technology is unique.

If I had to pick a symbol for the elder millennial condition:

It’s sometime around 2000 or 2001. I take my Compaq iPAQ 64 MB MP3 player (later my early-gen iPod) and plug into the tape deck of my mom’s Toyota. On one hand, this translation from digital to analog feels like a slick hack to bring the 20th century automobile into the new millennium. On the other hand, it feels really stupid. Like, viscerally dumb. With hindsight, I understand why: this was my first real taste of “friction.”

Friction is resistance where we know technology could promote fluidity; inefficiency and hardware waste where software could speed up outcomes, improve the quality of those outcomes, and pave the roads to reach them. In other words, more friction = worse UX.

Just before the mp3-to-tape converter days, I’d spend hours in my room toiling away beside a tower of CD-RWs. Burnin’ and rippin’. I could source and catalogue an enormous amount of music using just my computer, but listening to that music when and where I actually wanted required I transfer it to polycarbonate discs, which in turn required I set up a small scale manufacturing process in my bedroom. The potential of digital abundance, stifled. Friction.

Another example: The wonder of early social media before mobile really came into its own. Once you’d experienced hanging out on AOL, loitering in obscure chat rooms and IM’ing your school crush, mobile texting felt like a serious regression, a step back to morse code. You wanna talk about friction? We learned to thumb-type on degraded keyboards: three clicks just to get the letter you wanted.

Believe me, it wasn’t cool,

[ 666 ] - O[ 55 ] - K[ *_ ] - ?And this was all happening at the very impressionable age when we celebrated (endured?) one of the greatest potential friction events of all time: Y2K. The media tried to warn us of instability in the tech-enabled infrastructure, sensationalizing fears that all the tech progress was happening too quickly — the bubble was going to burst and the stock market would be the least of our problems. We went to bed at the end of 1999 thinking our computers might in fact be the bugs that would destroy the amazing systems they’d helped us build. But the world didn’t crumble.

For the elder millennial growing up in the 90s and early aughts, the actual friction of an average task — the energy required to communicate or complete a transaction or store information — was receding. But experienced friction increased. Friction became palpable, everywhere, because of high contrast: Take any device or system, and the best digital element within it made all other components or compatible devices that it sat alongside feel anachronistic. [A tangent, if you want to go there: inspo around the idea of experienced friction came from Kahneman et. al. on experienced utility.]

I think of us as the “Transitional Tech Generation.” A user’s experience of the technology of the age was historically unique: On a daily basis, with any given device, users were more than likely forced to have one foot in the future and one in the past, straddling digital and mechanical or analog realities.

Another way of thinking about it: Our adolescence coincided with technology's adolescence, if you look at technology on a long enough timescale.

Like the young adult who grew five inches over the summer and whose voice dropped an octave overnight, we could feel the acceleration of technology and the awkwardness it imposed on our lives despite its gifts. We became hyper-aware of the relationship between innovation and obsolescence. The tech mediating so many of our experiences gave us glimpses of magic, and yet even those of us without any technical chops somehow just knew the tech was suboptimal. And so we became adults highly motivated to pull the future forward, to drape the digital over all remaining analog touch points. We did this not in the name of societal progress, but to ease the frustration of living in a transitional era.

If boomers had Hendrix’s distorted Star Spangled Banner to soundtrack the tension of the time, we had the screeching dial-up tone, our national anthem of Friction. Elder millennials, the “Transitional Tech Generation,” were trained to be obsessed with overcoming friction and went on to set the precedent that contemporary UX design is first and foremost about friction-reduction.

II. Awakening to less obvious, more abstract opportunities to reduce friction

Just look at that sharp rise in the S&P from 2010 to 2020! One might explain the chart by saying we prevailed in our battle against friction. Software began to eat the world, and along the way the world learned of a powerful new economic lever: zero marginal cost of improved experience. The FAANGs formed the Mount Rushmore of friction-reduction.

To some, the primacy of UX is completely obvious, especially against the backdrop of the last decade of value creation. But many still regard UX design as the polish of the architecture (it’s all about aesthetics and optimizations to interfaces, the design of the minutiae). Or, they value UX design but don’t consider themselves to be in the business of “UX.”

Why?

We tend to conflate user experience with usability, and lots of thinking about friction gets pegged to this limited definition of UX. That distracts us from seeing tons of friction-trapped value to unlock.

Let’s call this the Bud Light effect, where “drinkability” is analogous to “usability.” Bud Light is the beer that makes you the most efficient consumer of beer that you can be. It does not enliven your palate, does not elevate a meal or an occasion. It reduces the friction of guzzling. And, look — that’s an achievement and a massive business. But that approach doesn’t translate well to software commerce; better usability is not defensible in a world where fluidity can be engineered and distributed with zero capex required.

Optimizing for drinkability/usability increases your TAM, but the opportunity cost is significant. You will lose consumers who want craft, who want to express their tastes, who want to understand something about the world — beyond their capacity to consume — through use of your product. Setting usability as the design standard keeps your product from delivering higher order benefits.

In the attention economy, that’s an important point. Available attention is scarce, producing and distributing media is easy and cheap, and therefore the marketing and comms arm of your business will struggle to outshine others if the muscle of that arm is all content and media dollars. The next generation of special companies understand that great UX is a serious marketing and branding flex. A product’s UX actually communicates a lot — both to the user and about the user who choses it over alternatives.

SNAP. #Roamcult. Stitch Fix. Just a few examples of companies for which UI/UX is a powerful “soft” moat, where user experience and brand are entwined.

The Airbnb backstory is also a great reminder of how an edge in UX can be *the* thing that catapults a startup from challenger company to world-changing business:

“...as much as people argue that Airbnb was a unique idea, it wasn’t. VRBO existed. Couchsurfing existed. Craigslist existed. It was very clearly an iteration of what was already happening.

...when the Airbnb story is told, it’s told as like ‘oh, people would never stay in each other’s houses, that’s crazy’...No, that was happening. That’s not crazy. That was happening before Airbnb started. Airbnb did not kick start that. They just built better tools than everyone else. They made it easier.”

-@mwseibel, Invest Like the Best podcast

Airbnb did not build the short-term rental market. If incumbents were competent, delivering usable apps to match supply and demand and facilitate transactions, Airbnb transcended competence by reducing friction a step further.

The “Transitional Tech Generation” grew up with a maniacal focus on friction-reduction, creating tons of value along the way by smoothing interfaces and transactions. But there’s more to unlock. There are layers to this thing.

Friction layers

We default to thinking of UX design as a specialization within a business. “UX” applies to the interfaces and services that a business develops and markets (subsets of the business). Invert that: What is the total interface of the business itself?

Think of the business at large as an API. What endpoints are available? How clear and crisp is the documentation? How well does your business mediate the exchange of data, dollars, or ideas among all parties it serves: customers, employees, and partners?

We’ve framed UX & friction in terms of how easy it is for the user to complete an action by interacting with a digital system, or how effectively software can help the user manipulate the physical world. These actions flow outward, fulfilling a user’s goal by extension and enabling an outcome outside of herself. What about reducing the friction of inward flows of value, like knowledge or emotional utility?

Friction can be an impediment to:

Taking a simple action

Moving or converting a resource, transacting

Understanding (comprehending or learning)

Trusting a person or an entity

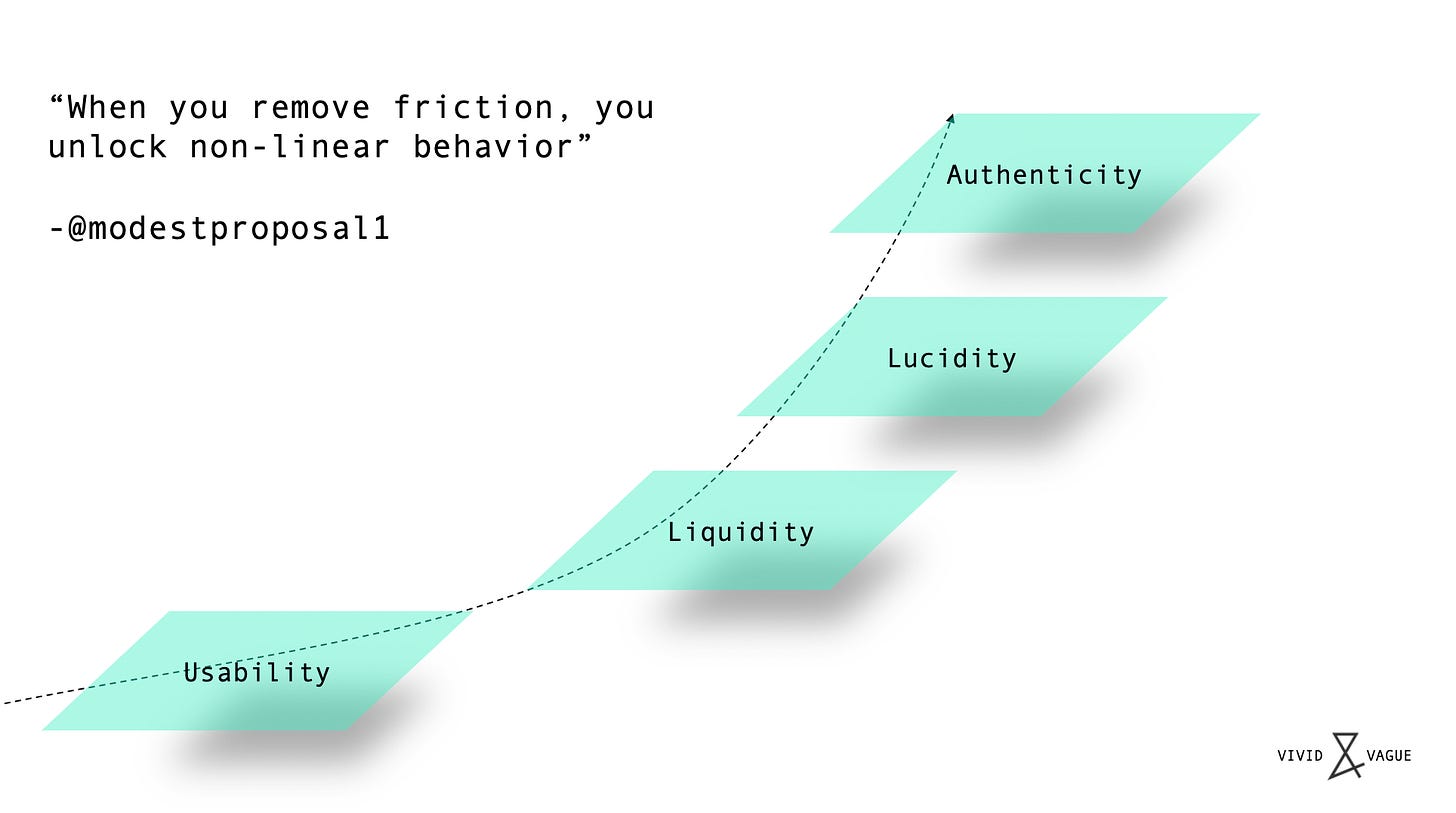

If we assign a quality to each of these layers, against which a product or brand can be assessed, it might look like this:

We’ve seen great companies form at layers one and two. Now, incredible businesses and brands are creating value and carving out identities at layers three and four. The “Transitional Tech Generation,” now building and problem-solving alongside younger counterparts, is awakening to the less obvious, more abstract opportunities for friction-reduction.

Let’s look at each layer:

1. Usability

Working definition [Wikipedia]: “The capacity of a system to provide a condition for its users to perform tasks safely, effectively, and efficiently while enjoying the experience.”

A smooth, logical onboarding flow. Sensible navigation and information architecture. Perceptible affordances. Messaging and design consistency. Usability is critically important, but it’s also a matter of housekeeping at this point. Better usability is not a defensible advantage.

2. Liquidity

Working definition: The availability of an asset or resource (tangible or intangible) and the ease with which it might be moved or converted to value in another form. The capacity to enable a high volume of value-generating activity.

(Obvious) examples:

Amazon: Search bar, one click to buy, and a physical item arrives at the door. Comparatively, everything else just kinda feels friction-full

Uber: Matching supply and demand, simplifying mobility transactions & mobility itself

Airpods: Seamlessly moving audio from devices to ears — not necessarily improving the audio itself, but removing an impediment to enjoying the audio in more contexts, thus unlocking many new hands-free activities with an audio backdrop

An interesting thought on the relationship between Liquidity & attention capture:

“Maybe the best modern way of thinking about business is just facilitating as many social or financial transactions between parties as possible, because around that ecosystem will come attention that can be monetized…”

-@patrick_oshag, Invest Like the Best podcast

As a business ascends friction layers, it overcomes logistical friction, reduces cognitive friction, and dissolves emotional friction.

3. Lucidity

Working definition: Clarity, intelligibility, comprehensibility; the quality of being easily understood. A lucid business is one that commits to legibility in all activities, internal and external. A business that doesn’t just sell or service, but one that elucidates.

No surprise here: Stripe is a prime example of a ‘lucid’ company. Rather than write my own take, I’m going to lift several points from the Not Boring newsletter analysis of Stripe:

Build an Excellent Product Experience. Stripe just works and adds delightful features over time.

Publish Great Content. Its API documentation is loved by engineers the world over. Stripe also publishes technology-related books and documentaries under Stripe Press. It seems a bizarre move for a payments processing tech company, but both show a commitment to progress, expertise, and a passion for high-quality communication.

Help Companies Get Their Start. Atlas allows companies to incorporate seamlessly...it makes a long, annoying, expensive process seamless.

Smart, Passionate, Public Employees. Stripe has attracted some incredible talent, and encourages them to publish their own thoughts on both related and unrelated topics freely. That sends signals to potential employees and customers that these are knowledgeable people you want to work with.

In this great Not Boring piece, @packym explains that the qualities outlined above have compounding effects. In other words, Stripe’s lucidity accelerates the rate at which the business can grow.

Lucidity lies in the details, too. This Twitter exchange I had with @BrianNorgard was about how seemingly small product or marketing details such as copy can produce a strong signal about a company’s lucidity:

What about a Lucidity counter-example? The HBO Max rollout comes to mind.

Unnecessarily confusing, opaque. A branding and product positioning decision that probably hinged on some “business case” rather than an intuitive consideration of the consumer experience. Regardless of whether or not we (the public) ultimately like the product, the more meta problem is that we can’t track HBO’s logic in this instance. It no longer seems like a brand that elucidates or reduces complexity in our world.

4. Authenticity

I’m going to hold back here for now — more on this in an upcoming essay, exploring the convergence of design and marketing. A few teaser thoughts:

Branding is increasingly a function of UI/UX. In a world of attention warfare, saturated by messaging, brands need to supply fluidity and experiential novelty in order to cut through.

If we are divided by media, messaging, politics — then UX is a channel through which to prove authenticity and unify audiences. Show, don’t tell.

Intention captures attention.

And, a final thought:

As a business ascends friction layers, it expands its offering from literal interfaces to abstracted interfaces.

Thanks for reading this week’s V&V. Did you enjoy? Get in touch on Twitter @marc_it. And tell someone else how Vivid & Vague can bring a strategic vibe to their inbox ✌️